How a Fundamental Design Flaw Robs Your Profits

by Randy Franiel, Compass Senior Accounts Manager, Canada

I had a call awhile back from a producer about a compression unit he’d bought (not from me) that was under-performing. $38 million a year under-performing! Got your attention? Yup, $38 million…

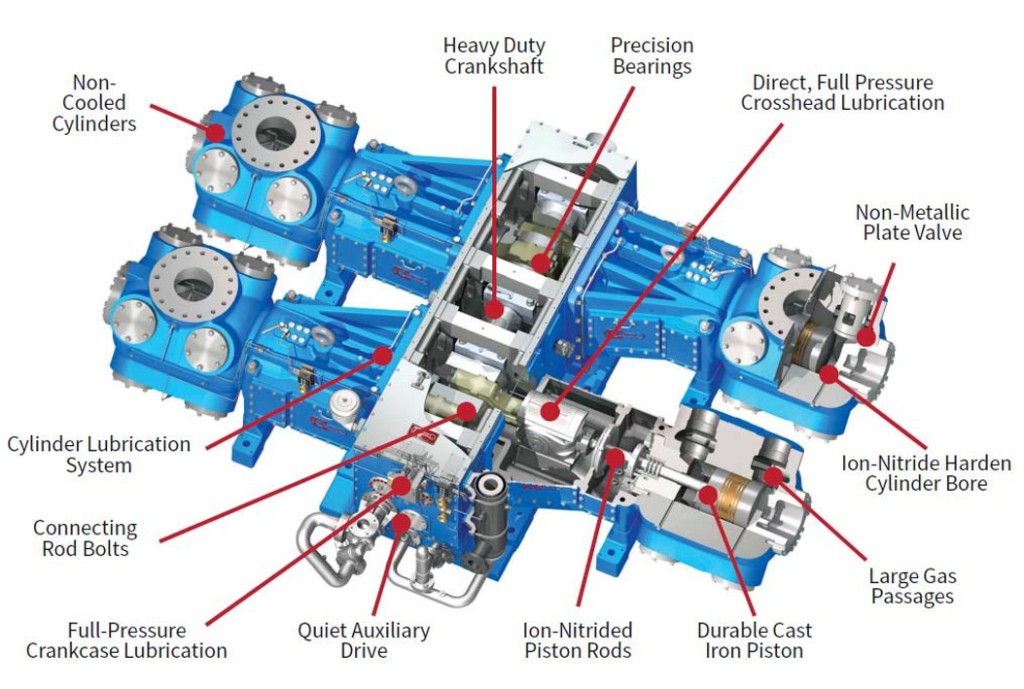

It wasn’t hard to diagnose the issue. This unit was under-performing for the very same reason many others do. Its performance was held back by a fundamental design flaw that had been there since day-one, that many compressor designers don’t fully understand… The compressor stroke was too long and the cylinders were too small.

I understand how it happens. When you’re sizing a new gas compressor, cost is important. Smaller is generally cheaper, so people choose a smaller cylinder and a longer stroke, but they don’t realize what it’s really costing them. This is a mistake and I’ll explain why.

The unit in question was an Ariel JGC4 (6.50” stroke), with four (4)7.25C10 cylinders. I compared its performance with an Ariel JGD4 (5.50” stroke), with four (4) 8.875” DK cylinders. Both units running at 1,000 rpm, and have the same Cat G3612A3 driver with 3550 bhp.

The only difference is that an Ariel JGD4 has a 1.00” shorter stroke. Why is this better? A shorter stroke requires bigger cylinders for the same displacement and, thus, is equipped with bigger valves. Bigger cylinders and more valve area allow the compressor to breathe.

Think of a valve as a port that you’re squeezing gas through. If the port is smaller and I’m putting a whole bunch of gas through it, it’s going to be less efficient. If that port is bigger and I push the same gas through, it’s going to be way more efficient.

The shorter-stroke machine, with bigger cylinders and bigger valves, breathes better. Result: you can flow more gas.

For both units, the inlet pressure or suction pressure is 1,025 psi. Both units are discharging at 1,752 psi. Given that, shouldn’t these two units ultimately flow the same volume of gas?

No, and it’s because of pressure losses through the valves. Any time gas goes through a port, there’s going to be a loss of pressure. The bigger the valve, the less pressure loss there is.

Comparing these two units, the smaller-cylinder, longer-stroke Ariel JGC4 loses 70 psi pressure during the process to get into the cylinder. The larger-cylinder, shorter-stroke Ariel JGD4 only loses 21 psi pressure to get into the cylinder.

Factoring-in this pressure-loss, the first unit moves 144 million cubic feet per day (MMSCFD) of gas. The second moves 164 MMSCFD. That’s a difference of 20 MMSCFD of gas. The difference in revenue, at a price of $3.50/mcf, is a staggering $38 million per year.

By avoiding this common and costly design flaw – cylinders and valves too small, stroke too long – producers can boost their revenue significantly. But it all starts at the beginning, what compressor, what stroke to use.

If you have questions about reciprocating compressors or gas compression,

please contact Randy Franiel by email or phone: 1-855-262-2487

Email Us

What you Need to Know About Reciprocating Gas Compressors

Have you read all the articles in our blog series?

Intro: What You Need to Know about Reciprocating Gas Compressors

Part 1: How a Fundamental Design Flaw Robs Your Profits

Part 2: Understanding the Importance of Shaking Forces

Part 3: Volumetric Efficiency: Why it Matters and How to Maximize It

Part 4: An Approach to Compressor Selection, and the #1 Issue to Watch For

Part 5: Your New Gas Compressor is Installed. Do THIS Before it Goes Online

Part 6: When Gas Compressors Operate Outside Design, Communication is Key